Science Fiction Films are

usually scientific, visionary, comic-strip-like, and imaginative, and usually

visualized through fanciful, imaginative settings, expert film production

design, advanced technology gadgets (i.e., robots and spaceships), scientific

developments, or by fantastic special effects. Sci-fi films are complete with

heroes, distant planets, impossible quests, improbable settings, fantastic

places, great dark and shadowy villains, futuristic technology and gizmos,

and unknown and inexplicable forces. Many other SF films feature time travels

or fantastic journeys, and are set either on Earth, into outer space, or (most

often) into the future time. Quite a few examples of science-fiction cinema

owe their origins to writers Jules Verne and H.G. Wells. Science Fiction Films are

usually scientific, visionary, comic-strip-like, and imaginative, and usually

visualized through fanciful, imaginative settings, expert film production

design, advanced technology gadgets (i.e., robots and spaceships), scientific

developments, or by fantastic special effects. Sci-fi films are complete with

heroes, distant planets, impossible quests, improbable settings, fantastic

places, great dark and shadowy villains, futuristic technology and gizmos,

and unknown and inexplicable forces. Many other SF films feature time travels

or fantastic journeys, and are set either on Earth, into outer space, or (most

often) into the future time. Quite a few examples of science-fiction cinema

owe their origins to writers Jules Verne and H.G. Wells.

See also AFI's 10

Top 10 - The Top 10 Science Fiction Films

They often portray the dangerous and sinister nature of knowledge

('there are some things Man is not meant to know') (i.e., the classic Frankenstein

(1931), The Island of Lost Souls (1933), and David Cronenberg's The Fly (1986) - an updating of the 1958 version directed by Kurt Neumann

and starring Vincent Price), and vital issues about the nature of mankind

and our place in the whole scheme of things, including the threatening, existential

loss of personal individuality (i.e., Invasion of the

Body Snatchers (1956), and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957)).

Plots of space-related conspiracies (Capricorn One (1977)), supercomputers

threatening impregnation (Demon Seed (1977)), the results of germ-warfare

(The Omega Man (1971)) and laboratory-bred viruses or plagues (28

Days Later (2002)), black-hole exploration (Event Horizon (1997)),

and futuristic genetic engineering and cloning (Gattaca (1997) and

Michael Bay's The Island (2005)) show the tremendous range that science-fiction

can delve into.

Strange and extraordinary microscopic organisms or giant,

mutant monsters ('things or creatures from space') may be unleashed, either

created by misguided mad scientists or by nuclear havoc (i.e., The Beast

From 20,000 Fathoms (1953)). Sci-fi tales have a prophetic nature (they

often attempt to figure out or depict the future) and are often set in a speculative

future time. They may provide a grim outlook, portraying a dystopic view of

the world that appears grim, decayed and un-nerving (i.e., Metropolis (1927) with its underground slave population and view of the effects of industrialization,

the portrayal of 'Big Brother' society in 1984 (1956 and 1984), nuclear annihilation in a post-apocalyptic world in On the Beach

(1959), Douglas Trumbull's vision of eco-disaster in Silent Running

(1972), Michael Crichton's Westworld (1973) with androids malfunctioning, Soylent Green (1973) with its famous quote: "Soylent Green IS

PEOPLE!", 'perfect' suburbanite wives in The Stepford Wives (1975), and the popular gladiatorial sport of the year 2018 in Rollerball (1975)).

Commonly, sci-fi films express society's anxiety about technology and how

to forecast and control the impact of technological and environmental change

on contemporary society.

A special subsection has been created on the subject of robots in film.

See:  Robots in Film (a comprehensive illustrated history here). Robots in Film (a comprehensive illustrated history here).

Science fiction often expresses the potential of technology

to destroy humankind through Armaggedon-like events, wars between worlds,

Earth-imperiling encounters or disasters (i.e., The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951), When Worlds Collide

(1951), The War of the Worlds (1953), the two Hollywood blockbusters Deep Impact (1998) and Armageddon (1998), and The Day After

Tomorrow (2004), etc.). In many science-fiction tales, aliens, creatures,

or beings (sometimes from our deep subconscious, sometimes in space or in

other dimensions) are unearthed and take the mythical fight to new metaphoric

dimensions or planes, depicting an eternal struggle or battle (good vs. evil)

that is played out by recognizable archetypes and warriors (i.e., Forbidden

Planet (1956) with references to the 'id monster' from Shakespeare's The

Tempest, the space opera  Star Wars (1977) with knights and a princess

with her galaxy's kingdom to save, The Fifth Element (1997), and the

metaphysical Solaris (1972 and 2002)). Beginning in the 80s,

science fiction began to be feverishly populated by noirish, cyberpunk films,

with characters including cyber-warriors, hackers, virtual reality dreamers

and druggies, and underworld low-lifers in nightmarish, un-real worlds (i.e., Star Wars (1977) with knights and a princess

with her galaxy's kingdom to save, The Fifth Element (1997), and the

metaphysical Solaris (1972 and 2002)). Beginning in the 80s,

science fiction began to be feverishly populated by noirish, cyberpunk films,

with characters including cyber-warriors, hackers, virtual reality dreamers

and druggies, and underworld low-lifers in nightmarish, un-real worlds (i.e.,  Blade

Runner (1982), Strange Days (1995), Johnny Mnemonic (1995),

and The Matrix (1999)). Blade

Runner (1982), Strange Days (1995), Johnny Mnemonic (1995),

and The Matrix (1999)).

Borrowing and Hybrid Genre Blending in Sci-Fi Films:

The genre is predominantly a version of fantasy

films ( Star Wars (1977)), but can easily overlap

with horror films, particularly when

technology or alien life forms become malevolent (Alien

(1979)) in a confined spaceship (much like a haunted-house story).

Quite a few science-fiction films took an Earth-bound tale and transported

it to outer space: Star Wars (1977)), but can easily overlap

with horror films, particularly when

technology or alien life forms become malevolent (Alien

(1979)) in a confined spaceship (much like a haunted-house story).

Quite a few science-fiction films took an Earth-bound tale and transported

it to outer space:  High Noon (1952) became Outland (1980), The Magnificent Seven (1960) was spoofed in Battle Beyond the Stars

(1980), Enemy Mine (1985) was essentially a remake of Hell in the Pacific (1968) with Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune, and the chariot race of High Noon (1952) became Outland (1980), The Magnificent Seven (1960) was spoofed in Battle Beyond the Stars

(1980), Enemy Mine (1985) was essentially a remake of Hell in the Pacific (1968) with Lee Marvin and Toshiro Mifune, and the chariot race of  Ben-Hur (1959) was duplicated in the pod-race

of Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999). Ben-Hur (1959) was duplicated in the pod-race

of Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999).

Further, there

are many examples of blurred or hybrid science fiction films that shared characteristics

with lots of other genres including:

The Earliest Science Fiction Films:

Many

early films in this genre featured similar fanciful special effects and thrilled

early audiences. The pioneering science fiction film, a 14-minute ground-breaking

masterpiece with 30 separate tableaus (scenes), Le

Voyage Dans La Lune (A Trip to the Moon) (1902), was made by imaginative,

turn-of-the-century French filmmaker/magician Georges Melies, approximating

the contents of the novels by Jules Verne (From the Earth to the Moon)

and H.G. Wells (First Men in the Moon). With innovative, illusionary

cinematic techniques (trick photography with superimposed images, dissolves

and cuts), he depicted many memorable, whimsical old-fashioned images: Many

early films in this genre featured similar fanciful special effects and thrilled

early audiences. The pioneering science fiction film, a 14-minute ground-breaking

masterpiece with 30 separate tableaus (scenes), Le

Voyage Dans La Lune (A Trip to the Moon) (1902), was made by imaginative,

turn-of-the-century French filmmaker/magician Georges Melies, approximating

the contents of the novels by Jules Verne (From the Earth to the Moon)

and H.G. Wells (First Men in the Moon). With innovative, illusionary

cinematic techniques (trick photography with superimposed images, dissolves

and cuts), he depicted many memorable, whimsical old-fashioned images:

- a modern-looking, projectile-style rocket ship blasting

off into space from a rocket-launching cannon (gunpowder powered?)

- a crash landing into the eye of the winking 'man in the

moon'

- the appearance of fantastic moon inhabitants (Selenites,

acrobats from the Folies Bergere) on the lunar surface

- a scene in the court of the moon king

- a last minute escape back to Earth

Otto Rippert's melodramatic and expressionistic Homunculus

(1916, Ger.) - mostly a lost silent film - was a serial (or mini-series)

composed of six one-hour episodic parts. It told about the life of an artificial

man (Danish actor Olaf Fonss) that was created by an archetypal mad scientist

(Friedrich Kuhne). The monstrous, vengeful creature, after realizing it was

soul-less and lacked human emotion, became a tyrannical dictator but was eventually

destroyed by a divine bolt of lightning. Its importance as an early science-fiction

film was that it served as a precursor and inspiration to Universal's Frankenstein

(1931) film and many other plots of sci-fi films (with mad scientists,

superhuman androids, Gothic elements, and the evil effects of technology).

The

first science fiction feature films appeared in the 1920s after the

Great War, showing increasing doubts about the destructive effects of technology

gone mad. The first feature-length dinosaur-oriented science-fiction film to be released was The Lost World (1925). It was also the first feature length film made in the US with the pioneering first major use (primitive)

of stop-motion animation with models for its special effects. It helped to establish

its genre - 'live' and life-like giant monsters-dinosaurs, later replicated

in Gojira (1954, Jp.), Jurassic Park (1993) and Godzilla

(1998). The

first science fiction feature films appeared in the 1920s after the

Great War, showing increasing doubts about the destructive effects of technology

gone mad. The first feature-length dinosaur-oriented science-fiction film to be released was The Lost World (1925). It was also the first feature length film made in the US with the pioneering first major use (primitive)

of stop-motion animation with models for its special effects. It helped to establish

its genre - 'live' and life-like giant monsters-dinosaurs, later replicated

in Gojira (1954, Jp.), Jurassic Park (1993) and Godzilla

(1998).

One of the greatest and most innovative films ever made was a silent

film set in the year 2000, German director Fritz Lang's classic, expressionistic,

techno-fantasy masterpiece Metropolis (1927) - sometimes considered

the  Blade

Runner of its time. It featured an evil scientist/magician named Rotwang,

a socially-controlled futuristic city, a beautiful but sinister female robot

named Maria (probably the first robot in a feature film, and later providing

the inspiration for George Lucas' C3-PO in Blade

Runner of its time. It featured an evil scientist/magician named Rotwang,

a socially-controlled futuristic city, a beautiful but sinister female robot

named Maria (probably the first robot in a feature film, and later providing

the inspiration for George Lucas' C3-PO in  Star Wars), a stratified society, and an oppressed

enslaved race of underground industrial workers. Even

today, the film is acclaimed for its original, futuristic sets, mechanized

society themes and a gigantic subterranean flood - it appeared to accurately

project the nature of society in the year 2000. [It was re-released in 1984

with a stirring, hard-rock score featuring Giorgio Moroder's music and songs

by Pat Benatar and Queen.] Star Wars), a stratified society, and an oppressed

enslaved race of underground industrial workers. Even

today, the film is acclaimed for its original, futuristic sets, mechanized

society themes and a gigantic subterranean flood - it appeared to accurately

project the nature of society in the year 2000. [It was re-released in 1984

with a stirring, hard-rock score featuring Giorgio Moroder's music and songs

by Pat Benatar and Queen.]

Another Lang film, his last silent film, was one of the first

space travel films, The Woman in the Moon (1929) (aka By Rocket

to the Moon). It was about a blastoff to the moon where explorers

discovered a mountainous landscape littered with raw diamonds and chunks of

gold. [The film introduced NASA's backward count to a launch - 5-4-3-2-1 to

future real-life space shots, and the effects of centrifugal force to future

space travel films.]

Alexander

Korda's epic view of the future Things to Come (1936) was directed

by visual imagist William Cameron Menzies and starred Raymond Massey (as pacifist

pilot John Cabal). The imaginative English film was based on an adaptation

of H. G. Wells' 1933 The Shape of Things to Come and set during the

years from 1940 to 2036 in 'Everytown.' It included a lengthy global world

war (WW II!), a prophetic Brave New World-view, a despotic tyrant named Rudolph

(Ralph Richardson), the dawn of the space age, and the attempt of social-engineering

scientists to save the world with technology. An attempt to prevent scientific

progress - and the launch of the first Moon rocket - was vainly led by sculptor

Theotocopulos (Cedric Hardwicke). David Butler's Just Imagine (1930),

a futuristic sci-fi musical about a man who awakened in a strange new world

- New York City in the 1980s, provided prophetic inventions including automatic

doors, test tube babies, and videophones. Alexander

Korda's epic view of the future Things to Come (1936) was directed

by visual imagist William Cameron Menzies and starred Raymond Massey (as pacifist

pilot John Cabal). The imaginative English film was based on an adaptation

of H. G. Wells' 1933 The Shape of Things to Come and set during the

years from 1940 to 2036 in 'Everytown.' It included a lengthy global world

war (WW II!), a prophetic Brave New World-view, a despotic tyrant named Rudolph

(Ralph Richardson), the dawn of the space age, and the attempt of social-engineering

scientists to save the world with technology. An attempt to prevent scientific

progress - and the launch of the first Moon rocket - was vainly led by sculptor

Theotocopulos (Cedric Hardwicke). David Butler's Just Imagine (1930),

a futuristic sci-fi musical about a man who awakened in a strange new world

- New York City in the 1980s, provided prophetic inventions including automatic

doors, test tube babies, and videophones.

Early Science-Fiction - Horror Film Blends: The 30s

The most memorable blending of science fiction and horror

was in Universal Studios' mad scientist-doctor/monster masterpiece from director

James Whale, Frankenstein (1931), an adaptation

of Mary Shelley's novel. Her original 1818 book was subtitled Frankenstein

- The Modern Prometheus, and she used this allusion to signify that her

main character Dr. Victor Frankenstein demonstrated 'hubris' against god/nature

in his experimental desire to create life from dead body parts, and afterwards

abandoned his monstrous ugly creature.  Like

the Titan god, who stole fire from the gods to benefit mankind, he did not

realize the ramifications of his actions. (Although there were civilizing

results of having fire, it also brought the ability to work with metals, which

could be shaped into weapons, that could then be used in warfare.) Many other

derivative works, including numerous sci-fi films, have featured mad scientists,

and artificially-created monsters that run amok killing people. Like

the Titan god, who stole fire from the gods to benefit mankind, he did not

realize the ramifications of his actions. (Although there were civilizing

results of having fire, it also brought the ability to work with metals, which

could be shaped into weapons, that could then be used in warfare.) Many other

derivative works, including numerous sci-fi films, have featured mad scientists,

and artificially-created monsters that run amok killing people.

This was soon followed by Whale's superior

sequel  Bride of Frankenstein (1935), one of the best examples of the horror-SF

crossover, and one of the first films with a mad scientist's creation of miniaturized

human beings. The famed director also made the film version of an H. G. Wells

novel The Invisible Man (1933) with Claude Rains (in his film debut

in the starring title role) - it was the classic tale of a scientist with

a formula for invisibility accompanied by spectacular special effects and

photographic tricks. Bride of Frankenstein (1935), one of the best examples of the horror-SF

crossover, and one of the first films with a mad scientist's creation of miniaturized

human beings. The famed director also made the film version of an H. G. Wells

novel The Invisible Man (1933) with Claude Rains (in his film debut

in the starring title role) - it was the classic tale of a scientist with

a formula for invisibility accompanied by spectacular special effects and

photographic tricks.

Mad Scientists in Early Horror/Sci-Fi Films:

In the 1930s and early 40s, American sound films with hybrid

science fiction/horror themes included an oddball collection of mad scientist

films, with memorable characters who created mutated or shrunken creatures:

The

Vampire Bat (1932) - a low-budget Majestic Pictures film in which Lionel

Atwill starred as mad doctor Otto Von Niemann, responsible for creating

bloodsucking nocturnal bats in a small German town; with a cast including

dark-haired, 'scream-queen' Fay Wray, Melvyn Douglas, and Dwight Frye (the

crazy Renfield character in Dracula) The

Vampire Bat (1932) - a low-budget Majestic Pictures film in which Lionel

Atwill starred as mad doctor Otto Von Niemann, responsible for creating

bloodsucking nocturnal bats in a small German town; with a cast including

dark-haired, 'scream-queen' Fay Wray, Melvyn Douglas, and Dwight Frye (the

crazy Renfield character in Dracula)- Doctor X (1932), a First National (later Warner

Bros.) film, in pioneering two-strip Technicolor by director Michael Curtiz,

about another mysterious mad scientist named Doctor X-avier (Lionel Atwill)

and his daughter (Fay Wray)

- The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933), another First

National film in two-strip Technicolor, about an insane, wax-dummy maker-sculptor,

again pairing Atwill and Wray, and featuring Glenda Farrell as a fast-talking,

wisecracking reporter; famous for the shocking 'face-mask crumbling' scene;

[re-made in 1953 as House of Wax with Vincent Price]

- The Black Cat (1934) - the

first and best of all the Karloff-Lugosi pairings at Universal, featuring

Boris Karloff (as a crazed devil worshipper) and Bela Lugosi (as a vengeful

architect)

- The Invisible Ray (1936) - although he usually played

a grotesque monster, Karloff starred as experimental physicist Dr. Janos

Rukh in this film; after traveling to Africa with his colleague Dr. Benet

(Bela Lugosi) and becoming infected by radiation (Radium X) in a meteor

of the nebula Andromeda, Karloff was transformed into a murdering, radiation-poisoned

megalomaniac as he hunted down his enemies and projected death rays at them

from his eyes (glaring from under a soft felt hat)

Tod

Browning's off-beat The Devil Doll (1936) - with Devil's Island escapee

and scientist Paul Lavond (Lionel Barrymore), disguised as a macabre elderly

woman ("Madame Mandelip"), vengefully terrorizing his enemies

by creating shrunken "devil dolls" to seek out his revenge; with

landmark special effects, and Maureen O'Sullivan in a supporting role as

Lavond's daughter Tod

Browning's off-beat The Devil Doll (1936) - with Devil's Island escapee

and scientist Paul Lavond (Lionel Barrymore), disguised as a macabre elderly

woman ("Madame Mandelip"), vengefully terrorizing his enemies

by creating shrunken "devil dolls" to seek out his revenge; with

landmark special effects, and Maureen O'Sullivan in a supporting role as

Lavond's daughter- Ernest Schoedsack's and Paramount's Dr. Cyclops (1940) - the first Technicolor horror/sci-fi film since The Mystery of the Wax

Museum (1933), with Albert Dekker as sadistic, bald, bespectacled mad

scientist Dr. Thorkel shrinking his victims in a remote Peruvian jungle

setting; the film received an Academy Award nomination for its Visual Effects

- The Monster and the Girl (1941) - another Paramount "B" horror/sci-fi film from director Stuart

Heisler, about eccentric mad scientist Dr. Parry (George Zucco) who transplanted

the brain of a wrongly-accused and executed murderer into a murderous gorilla,

who then went on a rampage to seek revenge

- director George Sherman's The

Lady and the Monster (1944) - the first film version of the classic tale Donovan's Brain by Curt Siodmak

[remade in 1954], in which the throbbing, telepathic brain of a dead and

unscrupulous industrialist/maniac named James Donovan was kept alive by

enthusiastic mad scientist/Prof. Franz Mueller (Erich von Stroheim)

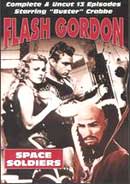

Escapist Serials of the 30s: Flash Gordon and Buck

Rogers

In the 1930s, the most popular films were the low-budget,

less-serious, space exploration tales portrayed in the popular, cliff-hanger

Saturday matinee serials with the first

two science-fiction heroes - Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers.

Space-explorer

hero Flash Gordon was a fanciful adventure character derived from the

Alex Raymond comic strip first published in 1934 (from King Features). The

serials 'invented' many familiar technological marvels: anti-gravity belts,

laser/ray guns, and spaceships. Universal's serialized sci-fi adventures included: Space-explorer

hero Flash Gordon was a fanciful adventure character derived from the

Alex Raymond comic strip first published in 1934 (from King Features). The

serials 'invented' many familiar technological marvels: anti-gravity belts,

laser/ray guns, and spaceships. Universal's serialized sci-fi adventures included:

- Flash Gordon: Space Soldiers (1936), the original

and the best of its type, with 13 chapters; later condensed into a 97-minute

feature film titled Flash Gordon: Rocketship

- Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars (1938) - 15 episodes

- Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940), 12 episodes,

with Carol Hughes as Dale Arden

Popular elements in the swashbuckling films were the perfectly-cast,

epic hero athlete/actor Larry "Buster" Crabbe, the lovely heroine

and Flash's blonde sweetheart Dale Arden (Jean Rogers), Dr. Hans Zarkov (Frank

Shannon), and the malevolent, tyrant Emperor Ming the Merciless (Charles Middleton)

on far-off planet Mongo. The Flash Gordon films were remade in 1980

(with Sam J. Jones as the title character and Max von Sydow as Ming, with

music by Queen), and in 1997 as the animated Flash Gordon: Marooned on

Mongo. [There was also a pornographic knock-off film titled Flesh Gordon

(1972) that featured a dildo-shaped spaceship.]

Wavy-haired, muscular Buster Crabbe also starred in the

12-part serial Buck Rogers Conquers the Universe (1939) shot

between Flash

Gordon's Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe

(1940). It was derived from the novelette story "Armageddon-2419

A.D." written by Phil Nolan (published in the August 1928 issue

of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories), and from the comic

strip Buck Rogers

in the 25th Century by Dick Calkins. In this sci-fi serial, Buck

Rogers pursued the vile Killer Kane (Anthony Warde), but the series

proved to be not as popular as the Flash Gordon serials.

Another serial was Republic's 15-part serial The Purple

Monster Strikes (1945), aka D-Day on Mars, with one of

the first instances of alien invasion. And in Columbia's 15-episode

serial Bruce

Gentry - Daredevil of the Skies (1949), the hero (Tom Neal) fought

off the genre's first flying saucers. |